Being a baby is confusing. A baby must constantly navigate a world that is unknown to them and interact with large creatures that act in unpredictable ways. These large creatures (adults) make strange garbled sounds, and act as if the baby is supposed to understand what they are saying. Adults have the power to change the environment, and even as you try to learn from them you are held back by the fact that they move too quickly for you to follow. They do each task differently each time, making it nearly impossible for you to determine what the correct procedure is. To make matters more difficult babies possess almost no physical strength and limited communication skills, making it difficult for them to exert their will on the world around them.

To help them navigate this confusing world babies are like little sponges. They explore their environment and the objects within it so they can gather valuable information. They do their best to determine what is edible and what is not, and test the limits of themselves, their surroundings, and the people they interact with.

The prevailing attitude for centuries was that babies are egocentric and irrational, and that they can only understand the world in concrete and limited ways. Modern advances in technology have determined that this limited and rigid view is false. In her book The Philosophical Baby (2009) Alison Gopnik wrote “Psychologists and neuroscientists have discovered that babies not only learn more, but imagine more, care more, and experience more than we would have thought possible. In some ways, young children are actually smarter, more imaginative, more caring and even more conscious than adults are.” These findings may appear revolutionary, but they would have come as no surprise to Dr. Maria Montessori.

Honoring the Process of Development

Dr. Montessori believed that “If the human personality is one at all stages of its development, we must conceive of a principle of education that has regard for all stages.” Rather than rely on the preconceived notions that dominated the field of early childhood learning Dr. Montessori combined her medical knowledge about anatomy and neurology with her observations on childhood. This led her to conclude that many of the previously held assumptions and prescribed responses to children and their behaviour was actually in direct conflict with human biology. When children are provided with environments that are in harmony with the process of their development what adults had previously labelled “misbehaviour” became a part of the learning process instead.

Montessori was one of the first philosophies that understood that a child’s mind and body continue to develop in the years after they are born. Who we become is largely dependant on how those first few formative years are spent, and what sort of physical encounters and experiences we have during that critical time.

Applied Sciences

A child that is suddenly too quiet tends to set off alarm bells in every parent’s head. By the time children are becoming mobile most parents have learned that a quiet child is likely doing something their caregivers will disapprove of. Dr. Montessori was fascinated by what children did when they were allowed to take the lead and interact with their surroundings free from adult interference.

By observing what children did when allowed to roam freely she discovered many sensitive periods of brain development. During these periods millions of neurons are being programmed so they can best perceive the stimulus found in their immediate surroundings, and the cognitive architecture for thought and action is being formed.

That is why she believed that a child’s drives should be encouraged, not thwarted, and that it was essential that parents, teachers and caregivers provide appropriate means for children to express those drives in a healthy way. She observed that industrialization had radically changed the childhood experiences that had developed naturally over the proceeding millennia. She made it her goal to restore and synthesize vital experiences full of physiological benefits and implicit information.

Sally Goddard Blythe, the director of the Institute for Neuro-Physiological Psychology echoed this sentiment in 2011 when she warned “One of the greatest threats to modern society comes not from diseases of the past (which medicine and hygiene have largely controlled), but illnesses, learning disorders and social problems, which are the direct consequence of modern living conditions, lifestyle, and ignorance of children’s biological needs.”

In her article Assessing Neuromotor Readiness for Learning Blythe laments that too many young children, toddlers and infants find themselves relegated to “containers” such as swings, infant seats, high chairs and playpens. These containers drastically limit their ability to move and explore their environments, and expose children to increasing hours of sedentary screen time. Children are both bombarded with noise and deprived of appropriate sensory experiences. Her research suggests that these modern cultural practices fail to support the maturation of the nervous, limbic and vestibular systems and also fail to inhibit primitive reflexes in accordance with optimal developmental timetables.

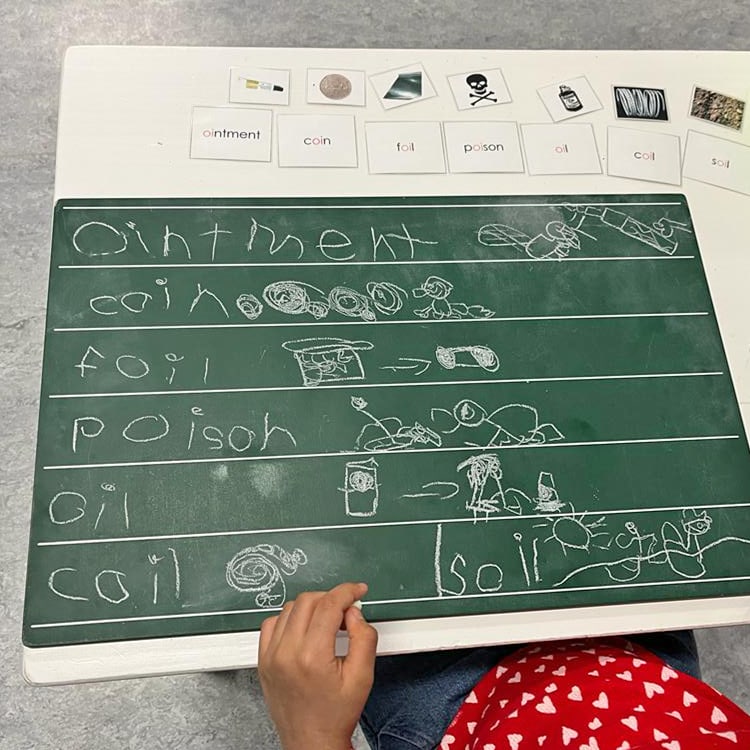

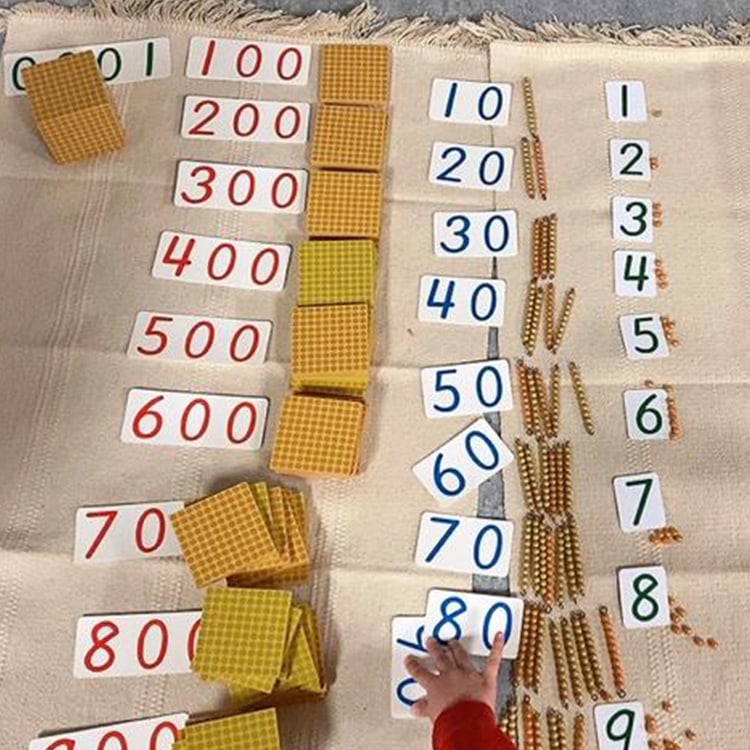

Dr. Montessori advocated passionately for children on these same topics, though she was limited by the language of her day. Her research linked freedom of movement to overall health. She observed that children loved to challenge themselves, and advocated for children to be provided with opportunities to struggle, develop their emotional strength, and improve their stamina. Children were able to better learn to categorize objects and concepts when provided with order and proximity, and that these exercises helped them learn skills related to memory and retrieval. An ordered environment also helped children better predict cause and effect – and pay attention to details for prolonged periods of time.

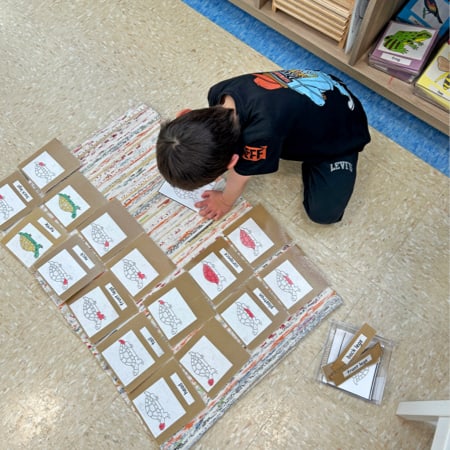

Children are better able to learn to make choices, and follow procedures and directions if events and objects are presented to them in a predictable order. This predictability also reduces anxiety and allows children to relax into the joys of childhood.

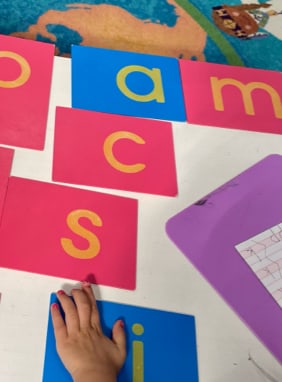

While Dr. Montessori could have left her observations at that she instead chose to develop an entire field of applied science to respond to the needs of human development. That is why materials and activities present in a Montessori environment follow a sequence that proceeds in order of use and complexity, much in the same way an artisan would order their tools. This allows children to proceed at their own pace, and explore their individual talents and interests.

Modern Research

When Darcia Narvaez addressed a 2012 symposium at Notre Dame she asked if today’s societies are “violating evolved expectations of care”, and compared cultures of the past to modern practices. One element of pre-modern caregiving that has recently received increased attention is the system of alloparenting, in which individuals other than the actual parents adopt a parental role. Human beings are unique because unlike most species we raise our children in communities. It is not uncommon for adults and children alike to ask if they can “hold the baby” at the first opportunity, and infants are often passed around to extended family members and friends in a way that reinforces a sense of social embeddedness and belonging.

The parent-child bond is undoubtedly essential, but the “It takes a village” axiom also holds true. Many researchers believe that the willingness of others to help care for a child makes it possible for mothers to eat and maintain their own strength. This sharing of caregiver duties allows not only for the mother’s children to benefit, but also helps ensure the survival of the species by extension. This idea does not imply that group sessions are suitable for all children, but instead speaks to the need for us to provide care and support to parents and families. The isolated nuclear family is a relatively new invention, which supplanted the large family systems of the past. In the past large extended families often shared childcare responsibilities amongst themselves, and children and adults often played and worked alongside one another.

In 1940 Maria Montessori said “The greatest mistake ever made is to isolate the child from the society of the adult, as has happened in modern times.” That is why in Montessori the first step in every stage of development is to allow the child to take in their environment holistically. The second part the child is encouraged to isolate and refine particular observed skills. Children learn through mimicry, and use their observations to internalize the rhythms of a successful and healthy daily life. The observation of adult work is critical as it allows them to overhear productive problem solving, learn how to collaborate and negotiate, and develop a nuanced “inner-speech” through example and mentoring.

We cannot turn back time, but we can modify our current child-rearing practices. Quality Montessori Infant/Toddler programs are founded on the concept of “home and family” in the very best sense of the terms. The goal of Montessori is to elevate the “natural mother”, who instead of scolding her children for getting into the clean laundry offers them a few washcloths of their own to work with. This spirit is at odds with the “watered down” Primary classrooms of mainstream education. Infant and toddlers who are taught using the Montessori method instead find themselves engaging in cleaning, cooking, handicrafts, gardening, reading, exercising and the general art of daily living. Montessori caregivers perform their actions with the utmost care, and are always aware of how their actions affect the children in their care.

In a Montessori environment you will find all manner of child-sized tools, provided so that the curious young minds may either work alongside the adults or continue the activity alone. This in turn satisfies the children’s need for repetition and the practice of basic skills.

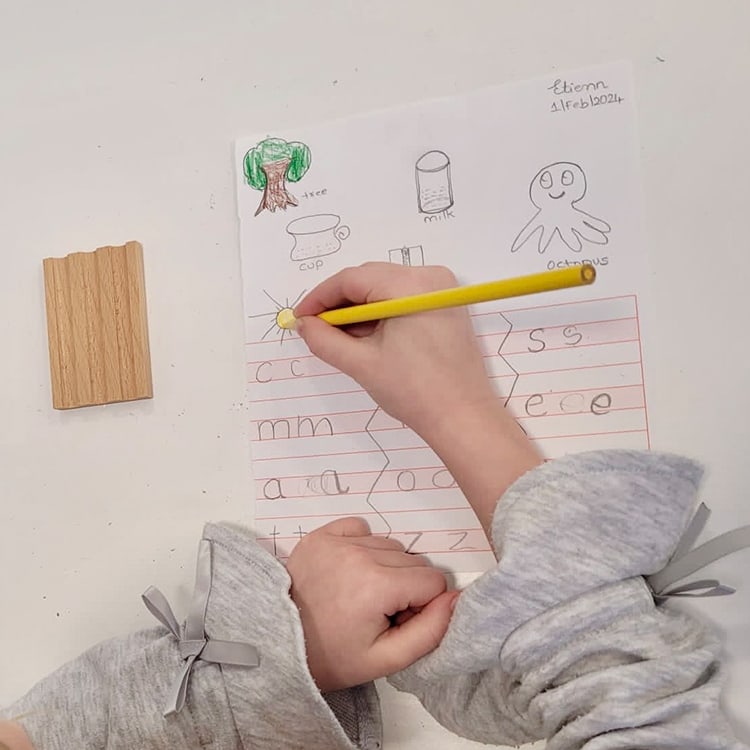

All toys and activities placed within a child’s reach in a Montessori school are carefully chosen to support their developmental needs. Objects are placed logically within the child’s environment, a choice that allows the child to gradually gain both experience and independence. Teachers always speak slowly, and are sure to articulate carefully as they describe shared activities and inform the children under their care about what they can expect to happen next.

Special Insight

When neuroscientist Jill Bolte Taylor experienced a stroke she underwent a life-changing event. During her ordeal she was returned to the world of infancy, and during her recovery she had to relearn everything she knew for a second time. Unlike babies, however, she was able to critically observe her experience and record her findings. As she recovered Taylor wrote a list of things that improved her recovery process. One of her requests was for “activities to be broken down into smaller steps of action” and to be told what the next step in the process was so she could adequately prepare herself for it.

She requested that caregivers “protect her energy”, and “be aware of what their body language and facial expressions were communicating to her.” She despised the intrusion of tv and talk radio, and asked for all activities be presented to her kinesthetically. She also requested that others be mindful that she would need to master one step before she could move on to the next one.

Above all else, she wanted to be treated like a person despite her diminished capacity. She asked others to be as patient with her during the twentieth try as they were with the first and to understand that if she was capable of learning faster she would.

It appears that all human beings, no matter how old or young, have an unshakable sense of dignity and personhood that suffers greatly when they are ignored or disrespected.

We should dedicate ourselves to helping those who are just beginning their lives to develop in ways that are optimal by responding to each child’s uniqueness as well as their neurological and biological needs. This idea is at the heart of Montessori philosophy, and is reflected in each prepared level of development.